I fell into doom scrolling along with everyone else. It was terrible. Then I started doing other things. I kept a guitar in every room of the house so that I could always be around one and put my phone down. I also kept paperbacks around for this reason. It was great. But, sometimes, I just wanted to sit and look at my phone. The Kindle app was not helpful for me, yet. It still isn’t. I started reading Arts and Letters Daily, which is exquisite, but so well curated that I could run out of things to read in an hour.

Then I discovered what I like to call “beautyscrolling.” I would look at my custom feed on Reverb, which showed me a lot of really wonderful instruments and a lot of great ideas. This newsletter was born of that, honestly.

What would happen if we used scraps of time to inspire us, rather than letting them be cancerous and expand to take up whatever time we don’t consciously prevent them from becoming?

It got me spending time looking at things and thinking about them, which also led to reflection. Why does my feed always have weird guitars? Why don’t I own anything normal?

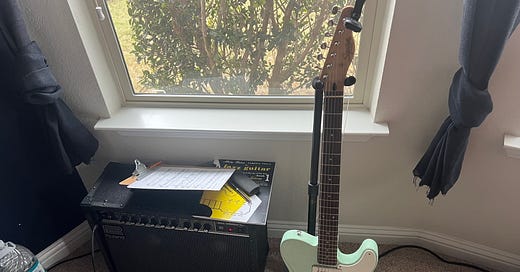

Six string guitars are amazing. I love them. I have a lot of them. But I also have a lot of unusual guitars that have an extended range, specifically, the lower range. I have a lot of seven string guitars, most of which are in Van Eps Tuning, which is standard tuning plus a Low A, and I have a baritone guitar with a low B. The baritone, is, of course, a Telecaster.

This thing is sick. Those P-90 style pickups take the growl that comes from a baritone, that lower range, and put a bell like chime on it, preserving the power of the low end, while putting the clarity and polish of the middle and upper ranges on it. It also doesn’t hurt that it’s played through a Roland JC-40, which is tremendous for clarity.

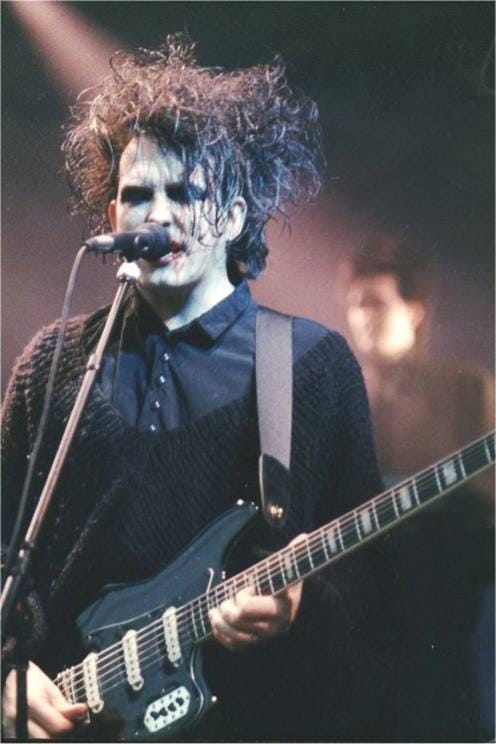

Between baritones and seven strings, the only lower range guitar that’s missing is the mighty Bass VI, made beloved to me by Robert Smith of The Cure.

These aren't the only lower range guitars I have. As I mentioned, I have some pretty amazing seven strings. Here’s my beloved Gretsch 7, for example.

It’s worse than you’d think. Every one of my guitars is strung up with heavy gauge flat wound strings or tape wound strings, which further emphasises the lower end. There is only one guitar in this house strung up with rounds, and it belongs to a friend of mine, he lent it to me for a bit because I love the way the weight sits.

So, why all the emphasis on the lower range? And if I like the lower range so much, why don’t I just play bass? These are some good questions, and I’ve had to really think about it.

The first answer is to the easiest question, which is that I do tremendously enjoy playing bass. It’s a lot of fun! But playing the bass is a fundamentally different task to playing the guitar. I think of the bass as translating rhythm into harmony, the primary relationships that the bass player has are to the drummer and to the harmonic instruments, the bassist sits in the middle. It’s very hard to play bass well. It is a skill unto itself, a profound one, at that, to be able to hear the rhythms and create melodies that are not only beautiful unto themselves, but able to generate the melodies of the other instruments, and also be rhythmically beautiful, at that. There’s a reason that everyone knows the names of the bassists in every great band.

Playing the bass is a beautiful job and one that I can do a mediocre job at covering, in a pinch, in the same way that a carpenter can probably help you repair your vacuum cleaner, in a pinch. But I don’t think like a bassist, I think like a guitarist. My job is to sit between the bass player, among the other harmonic instruments, and create the colours that soloists work against. I put colours on the moving foundation of the bass, that’s what I think about. So, my mind goes towards hearing the outer voices, the bass and the soprano, and creating the inner voices. I don’t think like a bassist, I think like a guitarist, and anyone who’s ever heard me play bass will tell you that I play bass like a guitar player. There’s an elegant minimalism to how bassists play that I will simply never have because it’s an alien role to me. Perhaps someone who is good at cooking Italian food can also make substitute and make a French dish, but you would never imagine that Antonio Carluccio could be a perfect substitute for Julia Child. Also, I am neither as good at what I do as either of them, but it’s important to understand that while some attributes are generally useful, allowing people to be competent in many domains, there is a value to domain specific expertise. A bassist is a bassist and is irreplaceable.

So, why the low end? Well, part of it is that I just like the way that it sounds. The if you think of upper frequencies as refining, and lower frequencies as constituting, a note that has a lot of bass has a lot of body to be refined, it’s like a rich, velvety custard, with a beautiful candied crust, as the treble. Crème brûlée! I like notes that have a lot of body, you can modify them on the amplifier or through the controls on the guitar, if you’re playing electric. Another reason that I like notes with a lot of bass is that the physical sensation of bass heavy notes is very different to the sensation to the sensation of mid-frequency heavy or treble frequency heavy notes. The latter have a piercing sensation, while the former land more percussively. When you feel the note hit your body, it’s very different.

Not only does having more bulk to define give you more range within which to define it, but the way that the note hits your body feels better.

But, there’s also the craftsman aspects of it. Having access to lower notes with a seven string guitar changes what kinds of melodies you can play, as well as chord voicings available to you, which means that you can cover different ground. Imagine that the chord on a beat is Amin7. Look at measure 1 of Fly Me To The Moon, the harmony is Amin7, which goes to Dmin7 in the next measure.

In an open mic or pickup band, normally, a bass player would cover the root or the third, which means that he would hit A or C in the first measure. Maybe he’d play around the melody notes, too.

In first two measures, the harmony notes are:

Amin7 - A C E G

Dmin7 - D F A C

The melody notes are, in order,

C B A G F | G A B [B]

So, it’s easy to imagine a bass line, moving in thirds and fourths, doing something like

C A G F | B F B B

You, as the guitarist, are free to do something anything else, while the pianist will do, well, everything. But, imagine, now, that your lower end overlaps the bassists upper end. You can play everything from A, up. Not only do your opportunities for chord voicings and inversions change, but, because you can cover those lower notes, what the bassist can play changes quite a bit. He’s free to express different notes, which can extend the harmony quite a bit.

Again, here are the melody notes,

C B A G F | G A B [B]

The bass line, could do something like finding ninths and elevenths of melody notes,

D A A B | A C A B

The overall effect of this sample line is to move as if we are in D Dorian. This becomes interesting because the key of the song is A Minor, whose relative major is C Major, in which D would move in a Dorian mode. So, now the bassist can not only play more interesting harmony notes to set the foundation, but he can imply the relative major, as well, using a mode.

Nothing stops him from having done that if you were on six strings, obviously, but few combos will tolerate that kind of harmonic adventurousness, most bands are risk averse and play what easily sounds pretty. For a bass player to step out without cover from the harmonic instruments can be beautiful, just ask Ron Carter or Charles Mingus, but there’s a reason we know those names, which is that they are the exceptions. Most bands just don’t do this. The guitarist covering essentials frees the bassist up to explore, rather than threading a needle, he’s dancing in a valley.

That’s the value of the lower range, which is great. So why note just re-tune? Surely, you can drop tune. We’ll get to that, but, before that, there is also another joy to playing these instruments. The necks and bodies on them are different, they tend to be much, much bigger, which means that you hold them differently, and your fretting hand moves very differently, accordingly. I don’t play fast lines or quick changes on a seven string, the bigger neck makes me move much more delicately. And on a baritone, not only is the neck wider, but the frets are spaced much farther apart, which changes, again, not only how you make chords and play lines, but your decisions about which chords and lines to play. You simply play these instruments differently, the physical differences make different choices valuable, in the same way that one walks through a forest very differently than one walks along a gravelly path.

In addition, retuning changes the string tension, which will impact how the string resonates when you pluck or strum it. You don’t want too much tension on the strings, but you want enough that it makes a clear sound. Dropping a guitar by a fourth, which is generally what a baritone gives you, would make it sound like mud if you played it, it would be floppy like a piece of cooked linguine. With a baritone or a seven, you get the resonances of tense strings, and you get different frequencies resonating like that.

The baritone and the seven accomplish similar ranges, but the baritone gets it by setting off the upper range and moving lower, while the seven string extends the range that a guitar can play. Both permit the lower end, but one is far more challenging than the other to play and is also much more suited for a solo guitar arrangement.

As a reminder, I have a few guitars that are standard tuning six string guitars and I love them, I absolutely love them. But my heart is really with the lower range girls.